About

Swarms can do things that no single individual can do alone. Robot swarms have, to date, been constructed from plastics, metals, and other artificial materials. Robots built from living materials instead of artificial ones (for example, using heart muscle) could offer numerous solutions to current challenges in robotics - such as the ability to biodegrade, a rich biochemistry for sensing and processing molecules, and the ability to self repair when injured. Here, we report living robot swarms, constructed entirely from amphibian skin cells. These self-powered living robots use tiny hairs (called cilia) on their bodies to rapidly swim through their environment, can be modified to record experience, and can work in groups to collect small objects in their vicinity. This new platform provides a faster way to manufacture large numbers of living robots, which can be used to study aspects of self-assembly, swarm behavior, and synthetic bioengineering, as well as provide versatile, soft-body living machines with practical applications in biomedicine and the environment.

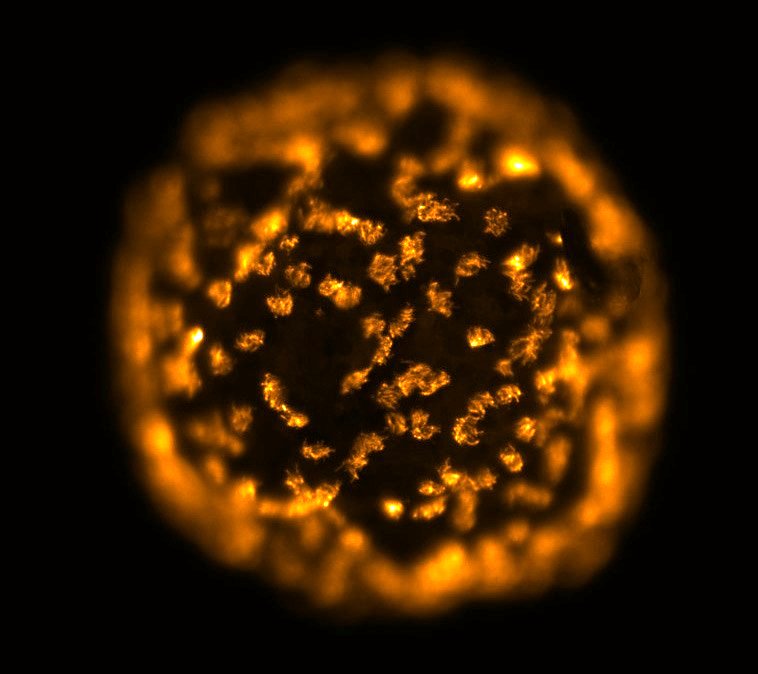

Cilia-driven swimming. Each individual living robot develops into a sphere, covered in cilia: thousands of waving hairs (glowing orange in the above image) that act as tiny oars to propel them through their aqueous environment.

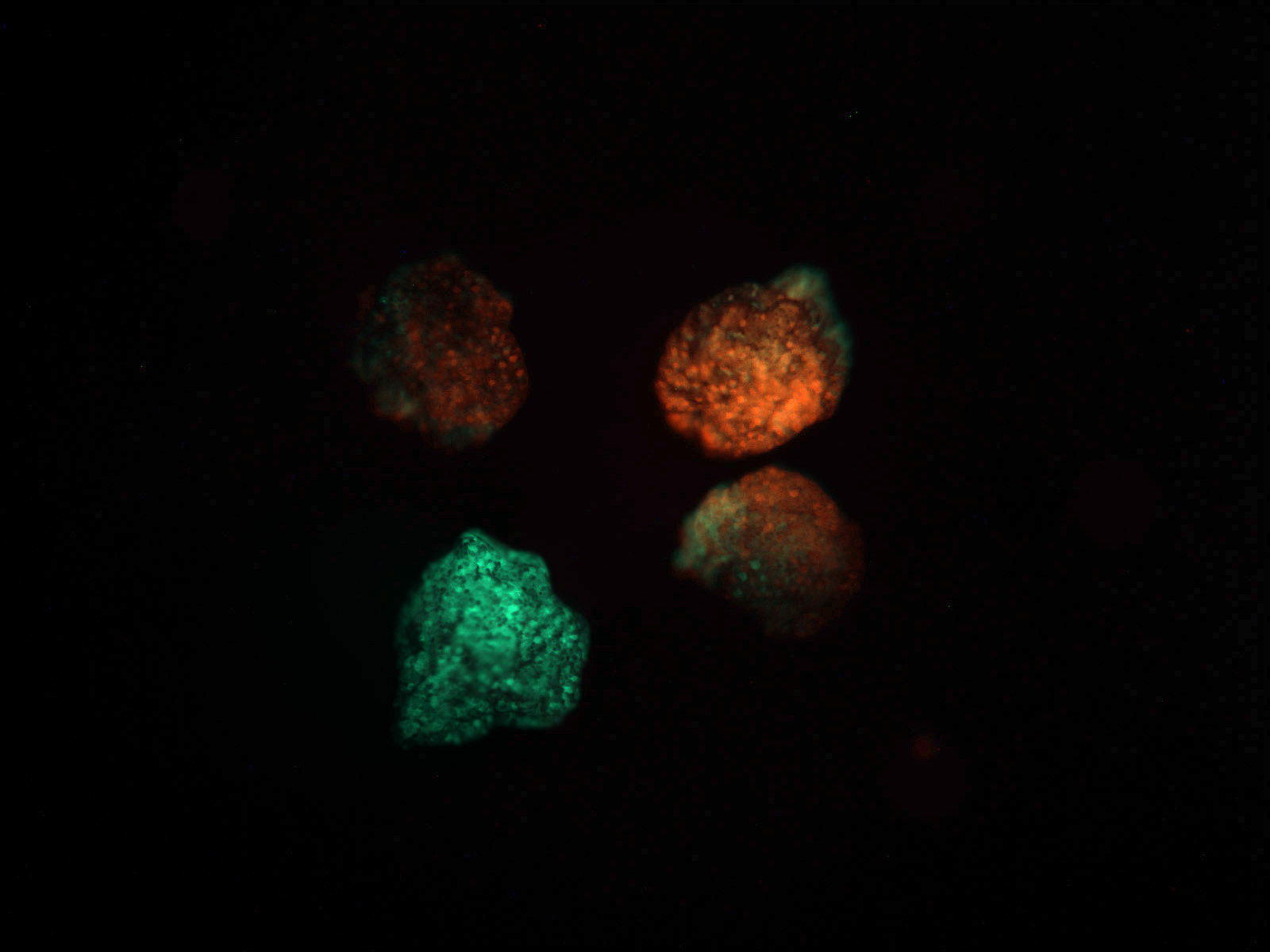

Go, see, remember, report back. An RNA molecule was introduced to the living robots to give them molecular memory: if exposed to blue light while swimming through their dish, they will glow red (when viewed under a fluorescent microscope) otherwise they glow green, indicating that they did not “see” the blue light.

How they’re made and what they can do:

A 1.5 minute summary video which can be downloaded with text overlay or without text.

Video credit: Douglas Blackiston.

FAQ

What’s new here?

The first xenobots paper was, at heart, a proof of principle that living robots exist, and that AI can design them to do simple things. This second paper investigates additional features and capabilities that could be incorporated into future living robots so that they may one day become useful machines.

Why robot swarms?

Groups of cells, organisms, and robots can complete tasks that an individual cannot perform alone. Swarms are robust to the loss or addition of units, and can work together to reduce the cognitive load and morphological complexity of individual agents, allowing the mass production of smaller, simpler, cheaper robots.

How big/small are they?

The living robots within a swarm vary from one quarter to one half of a millimeter: about the size of a fine grain of sand.

What can they do?

We’ve built living robots which can swim through their environment using tufts of hair like structures on their surface. These self-propelled organisms can swim through mazes, move through 0.6mm (.02in) tubes, heal from injury, and record information about their environment. When placed in large groups, swarms of living robots are able to gather particles/objects in their environment.

How do they have memory?

Using a RNA molecule introduced to the living robots, they appear green when viewed under a fluorescent microscope. However, if exposed to blue light, they will permanently change color red, which allows investigators to retrieve a molecular memory of bot experience as they swim around their environment. In the future, we plan to expand this method to allow our living robots to sense, and record, many different stimuli across their lifetime.

Are they aquatic?

Our living robots can live in freshwater and brackish water, and can tolerate temperature ranges of 4°C (40°F) to 26°C (80°F).

How long do they live?

The living robots can survive 10-14 days without food, consuming the energy preloaded in the frog egg (similar to the yolk of a chicken egg). If given an external food source, in the form of a sugar rich media, they can survive for a period of months.

What happens when they die?

A major benefit of living robots is that they are biodegradable. At the end of their lifespan they fall apart and break down in the water.

Can they reproduce?

The living robots cannot reproduce - they contain no reproductive cells (their composition is 100% somatic tissue).

Why do you call them “living robots”?

These organisms are created in a similar way to a traditional robot, using cells and tissues as materials from which to ‘build’ the structure/form and create predictable behavior. We also employ simulation and modeling in our studies to speed up the design process and solve numerous technical challenges.

How are these different from biohybrid robots?

Biohybrid designs contain both biological and artificial components, our designs are made entirely out of living cells.

Are there environmental applications?

There are numerous environmental challenges that would benefit from a programmable living robot. These include biosensing (recording exposure to pollutants or contaminants in a waterway), bioaccumulation (collecting molecules or materials such as microplastics, which we could then extract from the living robot), and bioremediation (seeking out and breaking down harmful chemicals). A major advantage is that our robots are entirely biodegradable.

Are there biomedical applications?

Medically, this technology could one day be used to build living robots from a patient’s stem cells, which could then help repair/regenerate damaged tissues, aid in targeted drug delivery, or even seek out cancerous tissues.

How is this possible?

Unlike traditional robots, these robots are built entirely from cells. The construction method to build three-dimensional living robots (each is made from ~3000 cells) was the focus of our first study, published in 2020 (see video above on ‘how are they built?’). The method used here to build swimming swarms requires much less shaping and intervention, greatly speeding up production.

Why is this important?

A living robot offers a number of advantages (as well as disadvantages) when compared to traditional robots. They are biodegradable, improving their use in environmental applications, and would be biocompatible if built from a patient’s cells. In addition, they are self-powered and are capable of repairing themselves when damaged.

What’s the computational advance?

We developed a GPU-accelerated physics engine to efficiently simulate tens of thousands of interacting biological and physical elements (cells and debris particles) that can be present within a single swarm of living robots. Hundreds of thousands of living robot swarms were simulated.

What’s the point of the simulations?

We used our new powerful simulator as a scientific tool to test hypotheses about the simplest control mechanisms required to achieve one of the behaviors that living robot swarms naturally exhibit: debris aggregation. We also used the simulator as a design tool to understand how to enhance debris aggregation, which might help future generations of living robot swarms perform useful work in the real world.

Besides the robotics aspect, what can we learn about biology?

An overarching biological question is how do cells cooperate to build complex, functional bodies? How can we control what they build, and what signals must be exchanged to create a specific morphology? This is important not only to understand the evolution of body shapes and the functions of the genome, but for all of biomedicine.